REFERRED PAIN: WHERE IS IT?

- Jul 11, 2019

- 8 min read

AUTHOR: SAMANTHA PANOS, PHYSIOTHERAPIST, BOUNCEREHAB

CO-AUTHOR: MATTHEW CRAIG, PRINCIPAL PHYSIOTHERAPIST, BOUNCEREHAB

CO-AUTHOR: JACK RAYMENT, PHYSIOTHERAPIST, BOUNCEREHAB

REFERRED PAIN

Pain doesn’t always mean that damage has occurred to the area of the body where it’s felt. (say what???) Sometimes when a body structure is injured or inflamed, pain can be perceived away from the site of damage. This interesting concept is called referred pain.

HOW DOES REFERRED PAIN WORK?

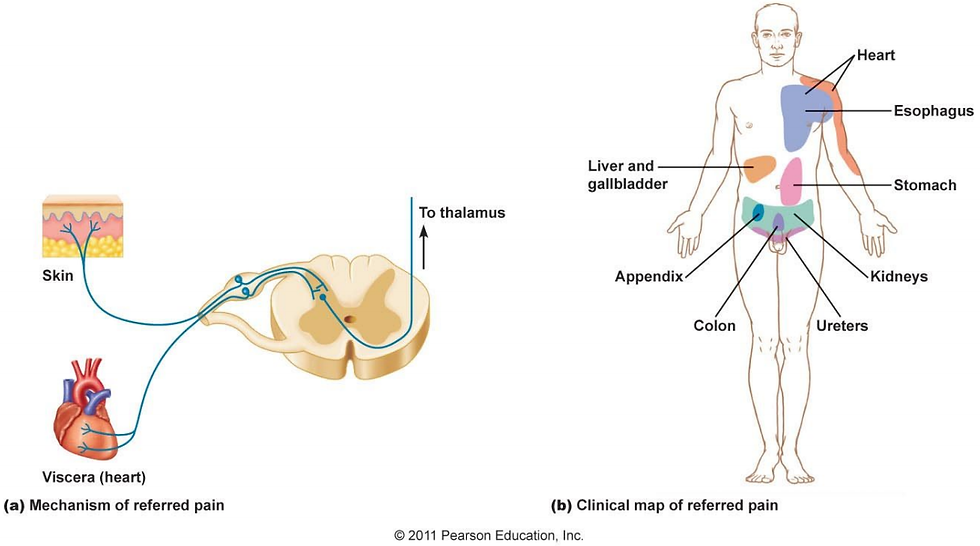

Pain can be referred elsewhere in the body from somatic (e.g. muscles or joints) or visceral (e.g. the heart, kidneys or liver) structures. The main theory behind referred pain is that the brain misinterprets the origin of a pain signal, causing you to feel it in an area away from the structure that is actually injured.

A QUICK 101 ON HOW PAIN INFORMATION IS DELIVERED TO THE BRAIN

1. A dangerous stimulus is perceived by nociceptors (danger receptors) located in the body (skin, organ, muscle, joint, etc)

2. These nociceptors are connected to pathways called peripheral nerves. The pain “danger” signal is sent from these nociceptors along the peripheral nerves, toward the spinal cord.

3. Groups of peripheral nerves originating from different body structures merge to form a spinal nerve. The pain signal enters the spinal cord via the spinal nerve.

4. The pain information is then sent up the spinal cord to the brain so it can be interpreted. *Note that pain hasn’t actually been perceived by the person yet! It’s still being processed at this stage*

so what’s the problem with this process?

At step 3 above, you’ll notice that the nerves connecting different body structures merge together to form a single spinal nerve that enters the spinal cord. This is called “convergence”. The problem with convergence is that when the brain receives a signal that there is potential injury occurring, it can’t differentiate which exact body structure the signal is coming from.

THE BRAIN CAN DETECT THE ORIGINAL SPINAL NERVE THAT SENT THE INFORMATION UP THE SPINAL CORD, BUT IT CAN’T TELL WHICH OF THE INDIVIDUAL PERIPHERAL NERVES IT CAME FROM.

Instead, the brain takes an educated guess in the context of past experiences- and is sometimes mistaken-so pain is felt at a point that is away from where the potential danger is actually occurring.

VISCERAL REFERRED PAIN:

You might be able to recall that left arm pain can be an indicator of heart attack. This is an example of visceral referred pain. The peripheral nerves responsible for transmitting sensory information from the heart (viscera) and the surface of the left arm both converge into the same spinal nerve. Due to this, the brain can’t tell whether a danger stimulus activated pain receptors from the heart or the surface of the left arm. The brain interprets the danger stimulus as coming from the left arm, as pain receptors are more frequently stimulated there rather than from the heart, even though in this scenario it’s the heart that’s under stress.

A CLOSER LOOK AT HOW PAIN IS INTERPRETED BY THE BRAIN…

I wouldn’t say referred pain is a no-brainer (ha!). Another theory behind referred pain is that it is due to the changing interaction of pain signals with pain “maps” in the brain(See Figure C below). Cortical maps occur in the somatosensory part of the cerebral cortex of the brain. Each map is devoted to the sensation of a specific area of the body– e.g. for the hand, the lips or the arms. The maps are linked to the nerve cells involved in our system of pain sensation- when a danger stimulus is sensed at a particular body site, area of the somatosensory cortex devoted to that area of the body lights up and is involved in interpreting the signal.

These maps can change according to how much a specific body part is used. This is called cortical reorganisation- or “smudging”. For example, the cortical map devoted to the fingers of a pianist would be much bigger compared to someone who didn’t play the piano. The opposite occurs too however- for example in an amputee. An individual who has had their arm amputated below the elbow for example, will not be stimulating the cortical map devoted to sensation of their hand or wrist because it’s no longer being used. While the body part has been removed, the cortical map for that area of the body still exists in the brain. Over time, smudging of the maps occurs, meaning that the adjacent elbow and upper arm maps will start to invade the cortical space originally devoted to the lower arm.

This means that pain signals that are meant to just light up the elbow map will also start lighting up the original map of the hand and wrist. This causes pain to be felt in the amputated limb- also called “phantom limb pain”. This is an important example of how the brain influences pain being felt in areas where there is no actual damage to the body structures (in this case because there isn’t even a limb there!), while the actual pain signal is coming from somewhere else.

SOMATIC REFERRED PAIN:

We’ve discussed visceral referred pain so far- i.e. how pain can be experienced in areas away from visceral structures (such as the heart), from which the actual pain signal originates.

A second type of referred pain is known as somatic referred pain. This regards pain signals originating from somatic structures (such as joints, ligaments, muscles), which are interpreted by your brain as pain in another area of the body.

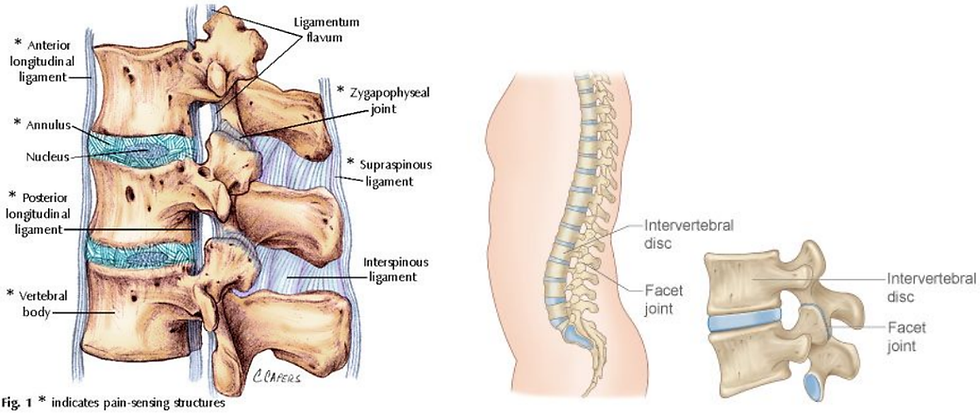

A common example of somatic referred pain is when pain is felt in the buttock, legs or foot following injury to a structure in the lower back.

Pain-sensitive structures of the spine include the:

Annulus fibrosus (outside layer) of the intervertebral disc

Facet (zygapophyseal) joints

Periosteum of the vertebrae

Dura

Epidural veins & arteries

LigamentsMuscles

Sometimes, pain is only felt in these referred areas (see below), rather than the lower back. It’s important for a health professional such as a physiotherapist to perform a comprehensive assessment to ascertain where the pain signal is originating from in the body so that area can be treated appropriately.

Another common example of somatic referred pain is seen when a patient comes in with chronic headache or pain radiating into the shoulders. Any pain generating structures innervated by the upper three cervical (neck) nerves (such as joints or intervertebral discs) which are injured, stiff or inflamed could be causing pain to refer to the head, eyes, neck or shoulders. For example in chronic headache, when a clinician assesses the mobility of these joints, they can commonly reproduce the headache that a patient experiences.

Head/neck pain following this pattern can be a result of stiffness of the C2/3 joint in the neck:

WHAT ABOUT TRIGGER POINTS?

Strained muscles often develop “myofascial trigger points”. Commonly known as muscle “knots”, they’re small bands of tightly contracted muscle tissue that are hypersensitive. When pressure is applied to active trigger points by a clinician, they can be extremely tender and cause pain at the site of pressure. They can also refer pain in a pattern that corresponds with where the patient reports feeling pain. For example, headaches can be a result of pain being referred from trigger points in surrounding neck and shoulder muscles. In these cases, relief from the headaches can be achieved when a clinician directs treatment to these trigger points.

WHAT ABOUT SCIATICA/NERVE PAIN?

Pain felt in the area away from the site of injury may also be due to the chemical irritation of nerves. This is called radicular pain. This pain is often sharp, shooting or burning – a common example is “sciatica”, where pain can be felt in the buttock and/or lower limb. The sciatic nerve originates from a collection of nerve roots in the sacral part of the spine (L4-S3), which converge into one single nerve in the buttock, and continues to extend down the back of the leg to the foot. Inflammation at any of these nerve roots can cause chemical irritation and pain extending along the pathway of the sciatic nerve. At times there may also be tingling/numbness due to compression of the nerve.

Another example is in hip osteoarthritis. Joint degeneration can lead to irritation of the nerve that supplies the hip (the saphenous branch of the femoral nerve)- causing radicular pain that radiates at and below the knee.

HOW A PHYSIOTHERAPIST CAN DIAGNOSE REFERRED PAIN:

Physiotherapists are trained to identify referred pain. Don’t be too surprised if you went into your first physio appointment with knee pain- and the physio starts assessing your hips and back! They need to assess the entire kinetic chain- i.e. they will look at the body structures above and below the area where pain is felt to get an idea of where the pain could actually be originating from. In some cases, pain may only be felt where it’s referred and not at the original site of damage- for example in paediatric physio, kids with transient synovitis or “irritable hip syndrome”, often only complain of knee pain. It’s therefore crucial for physios to take a look at the whole body during their assessment.

It’s important to remember that both locally originating and referred pain can occur at the same time. For example, in a lumbar intervertebral disc pathology the patient may feel pain in the centre of the lower back . They may also experience pain referred into the buttock due to misinterpretation of the pain signals (somatic referred pain), and with inflammation around the area, irritation of the nerves in the area can cause a narrow band of pain to run down the leg (radicular pain).

The true source of the pain must be identified and targeted in treatment, otherwise it may have no effect and prolong the patient’s pain experience. Often in both somatic and visceral referred pain, there is an exaggerated pain response (hyperalgesia) in the area where the pain is referred.

Common symptoms:

Symptoms remain unresolved with treatment performed where the pain is felt

You experience less tenderness than expected when the site of pain is palpated

There is pain in two different body sites, but there is a relationship between the symptoms- e.g. they are both aggravated at the same time by sitting

Referred somatic or visceral pain is often:

dull, aching, “gnawing” in quality

difficult to pinpoint, may follow a somatic referred pain pattern of distribution (see below)

Deep-seated

Longstanding

Common somatic referred pain patterns when the pain receptors of lower back interspinous ligaments are stimulated:

Radicular pain often:

Has an electric, lancinating quality, following a “dermatomal” pattern of distribution (see to right)

E.g. The narrow band quality of radicular pain due to irritation of the L5 spinal nerve

Is accompanied by changes in skin sensation such as pins and needles, or muscle weakness (in some cases where there is nerve compression)

Is sharp, shooting and travels along the limb in a narrow band (unlike somatic/visceral referred pain, which is more diffuse, spanning across multiple “dermatomes”)

HOW BOUNCE REHAB CAN HELP TO MANAGE YOUR REFERRED PAIN:

Physiotherapy

Aims of treatment are dependent on the cause of the referred and/or radicular pain, and may include:

Identify the underlying pathology

Control and reduce pain

Provide education and advice on how pain works, and strategies for self management

Provide safe and individualised treatment

Physio treatment options:

Pain science education

Dry needling

Soft tissue therapy

Joint mobilisation/manipulation

Neural mobilisationsI

ASTM

Clinical pilates / exercise therapy

Workplace ergonomic advice

Electrical stimulation

Real time ultrasound feedback

Taping, cryotherapy/heat therapy

Remedial massage

To help aid relaxation and relieve muscle spasm

Nutrition/Naturopathy

BioCeuticals supplements & products: Fish oil: anti-inflammatoryChondroplex: for healthy joints

Theractive: an anti-inflammatory & analgesic (pain reliever

)UltraMuscleze: magnesium for healthy muscles Magnesium sulfates (dissolved in a bath): for muscle health

RESOURCES:

Fernandez-de-Las-Penas, C., Simons, D., Cuadrado, ML., & Pareja, J. (2007).

The role of myofascial trigger points in musculoskeletal pain syndromes of the head & neck. Oct;11(5):365-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17894927

Brukner P., Khan K. Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2006.

De Koster, K. Referred pain- Physiopedia. Retrieved August 8, 2016. http://www.physio-pedia.com/Referred_Pain

Smale, S. (2014). The Cloward Sign..Cervical Referred Patterns. Retrieved August 8, 2016. lhttp://www.raynersmale.com/blog/2014/10/2/cloward-sign-neck-pain

Schoensee, SK., Jensen, G., Nicholson, G., Gossman, M., & Katholi, C. (1995) The Effect of Mobilisation on Cervical Headaches. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physiotherapy..http://www.jospt.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2519/jospt.1995.21.4.184

Bogduk, N. (2009) On the definitions & physiology of back pain, referred pain and radiculopathy. The Journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain. http://journals.lww.com/pain/Citation/2009/12150/On_the_definitions_and_physiology_of_back_pain,.9.aspx

PDF available here: https://rwillisdpt.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/bogduk-2009-on-the-definitions-and-physiology-of-back-pain-referred-pain-and-radicular-pain.pdf

Giamberardino, MA. (2003) Referred muscle pain/hyperalgesia and central sensitisation. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12817663

Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Svensson, P. (2001). Referred Muscle Pain: Basic and Clinical Findings. The Clinical Journal of Pain. http://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/Fulltext/2001/03000/Referred_Muscle_Pain__Basic_and_Clinical_Findings.3.aspx#P137

The Master Illusionist: Principles of Neuropsychology by Federico Sanchez (2010).

Khan, AM, McLoughlin, E., Giannakas, K., Hutchinson, C., & Andrew, JG. (2004). Hip Osteoarthritis: Where is the Pain? The Royal College of Surgeons, England. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1964166/pdf/15005931.pdf

Cor-Kinetic Blog. (2013). The brain, movement and pain! Part two. Retrieved August 8, 2016. https://bencormackpt.wordpress.com/2013/01/22/the-brain-movement-and-pain-part-two/

Jackson, MA., & Simpson, KH. (2004). Pain after amputation. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. http://ceaccp.oxfordjournals.org/content/4/1/20.full

Wang, E., & Wang, D. (2014). Treatment of Cervicogenic Headache with Cervical Epidural Steroid Injection. Current Pain and Headache Reports. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4148620/

Comments